https://seekingalpha.com/article/4242363-precious-dollars

Summary

- The money we CANNOT afford to lose.

- From a paycheck to your pocket.

- From your pocket to the piggy bank.

- Start early, start small.

- When taxation works for us.

What does counting pennies have to do with keeping and growing a family fortune?

My fiancée Megan and I recently spent an entire evening watching an old movie while counting coins. We’d been letting them collect in an oversized fishbowl. Megan had run to the bank earlier that day to get paper tubes to sort the denominations. I know there are easier ways to do it, but we wanted to have some fun with it. We were both eager to know how much we had amassed. Among hundreds of coins, we found one big surprise that made it all worth it! More on that in a little bit.

The money we CANNOT afford to lose

That experience made me think of the process of saving and building capital. It also reminded me how precious that saved or inherited capital really is, and how difficult – maybe even impossible -- it might be to replace. Any inheritance represents the savings of past generations. Each dollar of inheritance or savings is a dollar that went through battlefield after battlefield, and each dollar required to replace it will have to take an equally grueling path.

With that humbling observation in mind, we at Sicart make each and every investment decision for the sake of the life savings or inheritance entrusted to us. We always say: “This is the money our clients cannot afford to lose” and we treat it with the utmost respect and care. This idea is unfortunately shared by fewer and fewer money managers these days. Among them, though, is the thoughtful Swiss-based investor Anthony Deden, who says this about family wealth: “Respect the fact that is really irreplaceable. It represents a lifetime’s worth of savings.”

From a paycheck to your pocket

Let’s explore for a minute that grueling path taken by each dollar of those savings before ending up safe in an individual’s bank account. That dollar probably starts as $5 or maybe even $10 on a paycheck. It’s slashed by an employer’s payroll tax contribution, and then by the employee’s payroll contribution, only to be taxed at the federal, state, and local levels. If you are a fortunate high earner in a high-tax zip code, the total taxes subtracted from your paycheck could amount to 15% (total payroll) plus 37% (federal) plus 12-13% (state and local). That’s as much as 65% (or almost two-thirds!) stripped away before you see your dollars. Each ten-dollar bill ($10) turns into three single dollar bills and 2 quarters ($3.50) at today’s marginal rate in the U.S. (It could be even less in some higher-tax countries around the globe.) If you now subtract the cost of living and a few modest pleasures, you could end up keeping as little as 20% of your pre-tax pay. (By the way, earning less to fall under a lower tax bracket doesn’t really promote our savings goal here.)

From your pocket to the piggy bank

For this hypothetical $2 out of each $10 earned, the metaphorical journey to the bank isn’t even over. The biggest obstacle is our undying desire to spend! Behind every dollar that’s been successfully saved are endless feats of self-denial or personal sacrifice. For a child, this might have meant no ice cream. In the adult world, sticking to a savings goal may mean keeping an old TV or an iPhone longer, driving an older car, or foregoing a family trip. These may be the wise choices but they’re hard to stick within a world where (as savings guru Dave Ramsey puts it) “We buy things we don't need with money we don't have to impress people we don't like.”

Start early, start small

Speaking of ice cream and childhood, the first money I saved was through a school savings plan. This was in the late 1980s Cold War Poland. We children were encouraged to put money away and monitor the progress of our savings in a little green book. (The plan was actually started in the 1920s, and continues in some form today.) On the back of the green book was the motto “Learn to save. Even little amounts can grow to big amounts.” Even communist Poland promoted the habit of saving money!

Listen to your Grandma

As meticulous as my little entries to the green book were, I learned my frugality less from government initiatives than from my cost-conscious Grandma. She had grown up during the hardships of WW2 and lean post-war years. Following her example, I hardly ever pay full price for anything, from a pair of shoes to a scuba-diving trip. (And believe me, she still asks and keeps track!)

Old ideas come back in style

Frugality is in fashion again, among young and old alike. For some it’s a conscious choice – they want to start a nest egg and worry less about the future. For others, already burdened with student debt, frugality is necessary. The FIRE movement is catching on: “Financial Independence, Retire Early.” Minimalism is shaping a new generation of consumers, while their parents downsize and learn the art of tidying up.

Why we can’t afford to lose it

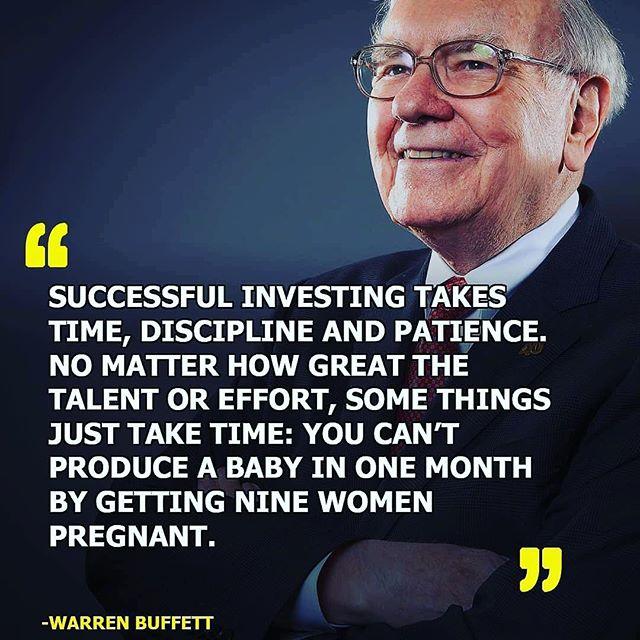

Every dollar of savings, whether inherited or squirreled away through personal sacrifices, is the money we just can’t afford to lose. Why? Because it is so hard to earn it, save it, and grow it all over again! Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s business partner, has been the source of much common-sense financial wisdom. In Damn Right!: Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger, author Janet Lowe writes:

"Munger has said that accumulating the first $100,000 from a standing start, with no seed money, is the most difficult part of building wealth. Making the first million was the next big hurdle. To do that a person must consistently underspend his income. Getting wealthy, he explains, is like rolling a snowball. It helps to start on top of a long hill—start early and try to roll that snowball for a very long time. It helps to live a long life.”

And it helps to remember the immense effort it took to climb there, and how painful it would be to do it all over again. How do we stay rich then? Here’s some more folk wisdom: “Rich people stay rich by living like they are broke. Broke people stay broke by living like they’re rich.”

When taxation works for us

Once you have savings or inheritance, it pays to invest it not just because money makes more money. In addition, the tax rates on long-term capital gains and dividends are substantially lower than taxes on earned income, in most countries around the world. In the US, for example, taxes on long-term investments are roughly half of the rates we pay on earned income. Thus, our invested capital compounds faster. That’s yet another incentive to save.

***

To go back to that fishbowl full of coins – Megan and I counted up a grand total of $255 in nickels, dimes, and quarters, quite a heavy load to take to the bank. Among hundreds of coins, we found a real treasure in the form of a 1940s quarter! It looked more tarnished than the later quarters and made a higher-pitched sound when dropped than the contemporary copper ones. It reminded me of the big heavy silver coins from 1930s Poland that my grandparents showed me when I was little – because U.S. quarters were made of 90% silver before the mid-1960s. So, the metal alone makes this quarter worth $3 today, 12 times what the denomination would imply!

Now, the big decision for us remains: what should we do with our casually accumulated $255? Obviously, the fishbowl is neither the only nor the main way we save, but the growth of capital felt very real and tangible that day. As Benjamin Franklin wrote, “a penny saved is two pence clear.” So let the money double, and let your nickels, dimes, and quarters turn into hundred-dollar bills, where Franklin is waiting for you with a smile. Turn those Benjamins into shares of companies that will grow and prosper over a lifetime.

If no inheritance is coming your way – start saving, and if you have savings or inheritance already treat them with the utmost respect and care – it’s the most precious dollars you could ever have.

They are truly irreplaceable.

Happy Investing!

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: This article is not intended to be a client‐specific suitability analysis or recommendation, an offer to participate in any investment, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell securities. Do not use this report as the sole basis for investment decisions. Do not select an asset class or investment product based on performance alone. Consider all relevant information, including your existing portfolio, investment objectives, risk tolerance, liquidity needs and investment time horizon. This report is for general informational purposes only and is not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, market sector or the markets generally.